Rare Earth Minerals are a group of 17 elements used in industry. Historically, they were not particularly sought after, but nowadays, they’re used in the production of many of the world’s greatest technological breakthroughs. Think aircrafts, vehicles, 3D imaging, sensors, self-cleaning ovens, sonar and wind turbines.

In recent years the US has imported nearly all its rare earth minerals from China, but with the US-China trade war intensifying over the past 4 years, the pandemic has shone a spotlight on just how reliant the US has become on its rival for this particular product. With the blessing of the Trump administration, it’s now on a mission to revive the mining of these minerals back on US soil.

#What are Rare Earth Minerals?

The Rare Earth Elements are the fifteen Lanthanide elements found on the periodic table, along with two related elements Scandium and Yttrium.

Image taken from Geology.com

Cerium (Symbol: Ce, atomic number: 58)

Dysprosium (Symbol: Dy, atomic number: 66)

Erbium (Symbol: Er, atomic number: 68)

Europium (Symbol: Eu, atomic number: 63)

Gadolinium (Symbol: Gd, atomic number: 64)

Holmium (Symbol: Ho, atomic number: 67)

Lanthanum (Symbol: Ln, atomic number: 57)

Lutetium (Symbol: Lu, atomic number: 71)

Neodymium (Symbol: Nd, atomic number: 60)

Praseodymium (Symbol: Pr, atomic number: 59)

Promethium (Symbol: Pm, atomic number: 61)

Samarium (Symbol: Sm, atomic number: 62)

Terbium (Symbol: Tb, atomic number: 65)

Thulium (Symbol: Tm, atomic number: 69)

Ytterbium (Symbol: Yb, atomic number: 70)

Scandium (Symbol: Sc, atomic number: 21)

Yttrium (Symbol: Y, atomic number: 39)

The advent of color television in the 1960s propelled the demand for rare earth mining, and demand has been soaring ever since. The biggest use for Rare Earth Elements is their ability to make incredibly powerful magnets. Nowadays, over 90% of electric vehicles use magnets made of rare earths and the F-35 fighter jet is a heavy user of them too.

A recent report by Adamas Intelligence forecasts that the value of the global magnet rare earth oxide consumption will rise fivefold by 2030, from US$2.98 billion this year to US$16.5 billion by the end of the decade. As a result, the supply of some rare earths is not keeping up with demand.

#Mountain Pass Mine in the Mojave Desert

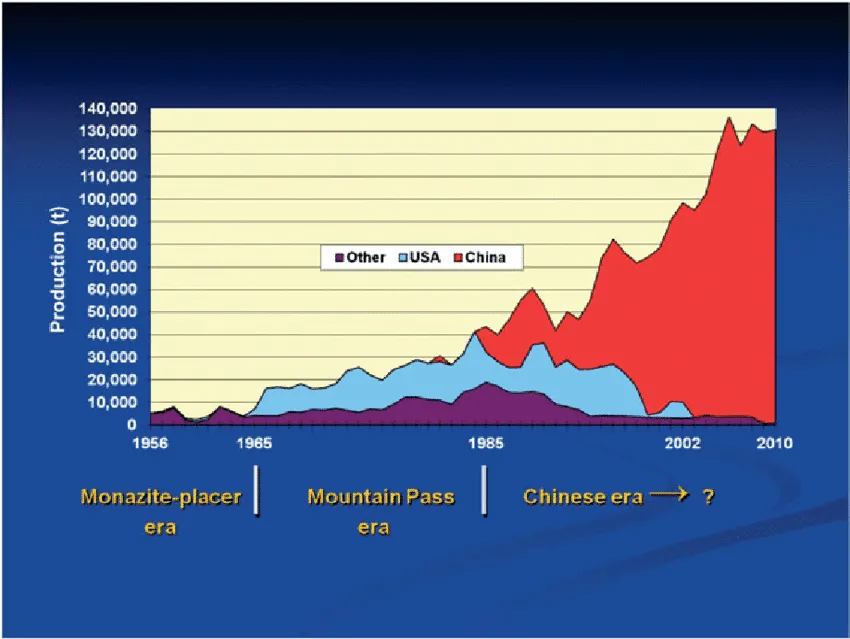

The trouble is, like anything mined out of the ground, these are finite resources, giving them added value. Therefore, control and ownership, matter. The only operational rare earth mine in the US is called Mountain Pass and can be found in the Mojave Desert in California. From the mid-sixties to the mid-eighties, Mountain Pass accounted for the majority of the world’s rare earth metal production. Today it accounts for one-tenth, with over 80% of the world’s production coming out of China.

The transition came about as manufacturers opted for the cheapest option, which, no surprise, turned out to be China. Some Chinese mines produce rare earths as a by-product, which adds convenience and provides another reason for its cheaper price point.

Image taken from MP Materials

The Mojave Mountain Pass mine was closed in 1998 after problems with toxic wastewater, and the site was abandoned in 2002. It’s now owned by MP Materials, who acquired it out of bankruptcy in 2017.

MP Materials recently merged with Fortress Value Acquisition Corp. (NYSE: FVAC) and is keen to progress rare earth mining in the US to drive domestic job creation, protect national security and propel a carbon-reduced future. Although it’s in production, it has to send its ores to China for processing.

Now that the pandemic has put the focus back on the importance of domestic self-sufficiency, many investors are calling for the Mountain Pass mine to be reinvigorated, and the Trump administration is backing this stance.

In April, the Pentagon selected MP Materials for a contract to produce a narrow class of heavy rare earth metals critical to military devices in a bid to restore production to the US. An Australian company was also awarded, but congress voted against this, arguing that funding should only be given to companies operating entirely in the United States.

Image taken from the US defense

#A threat to national security

At the moment China controls the vast majority of the US and the rest of the world’s critical rare earth supply chain placing every weapons system at some level of risk. Then, last year, during one of their many recurring trade spats, China threatened to stop exporting rare earths to the US.

This had industry and investors up in arms, with Billionaire investor Ray Dalio commenting that refined rare metals are a critical import that the US needs for many of its highly utilized products, including mobile phones, gyroscopes, LED lights and ceramics. The oil industry is also reliant on rare earths in its refining processes.

In 2010 China fell out with Japan and embargoed its Rare Earth Elements exports. It wasn’t as big a disaster as many expected; Japan adapted and imported from elsewhere. Therefore, while being cut off would cause short-term problems, it’s not as worrying as the potential security threat.

It’s now being argued that bringing production back to the US is not merely useful, it’s vital to national security. The defense sector is a key consumer of Rare Earth Elements, but under China’s control it seems this puts US defense in a perilously worrying position.

Considering the recent uproar regarding Huawei infiltrating US telecoms, that seems small scale compared to the reality check of China potentially placing every weapons system at some level of risk. Tensions are already running high between the two great nations; increased conflict is certain to raise security concerns and suspicion. Replacing the Chinese supply chains is no mean feat; it will take years to achieve and large amounts of capital. But if the government is willing to foot the bill in the name of security, then it may well happen.

#From Shale to Rare Earth Elements

Twenty years ago, few could have dreamt that America would create its own shale revolution, but it defied the odds, and in the process, many fortunes have been made (and lost). Back in 2006, the US imported 60% of its oil, but by 2015 it had overtaken both Saudi Arabia and Russia to become the world’s largest producer of oil and natural gas. Unfortunately, it went wrong this year when Saudi-Arabia slashed its prices causing the price of oil to plummet. Of course, that’s not been the only cause of the oil price crash, Coronavirus has eliminated demand and OPEC+ reduced production. Nevertheless, could China pull a similar stunt with regard to slashing the prices of Rare Earth Elements?

Yes, is the simple answer. In fact, it has already done this. After hiking prices in 2010, driving US innovators to look closer to home, it then caused prices to plummet, to discourage US progress.

In 2011 Molycorp was the only American company producing rare earths, out of the Mountain Pass mine. The Pentagon backed it and investors piled in on the belief US production would soon be soaring and Molycorp’s share price with it, but sadly, this was not to be.

At first shareholders saw their investments soar. When Japan started looking elsewhere for imports, Molycorp was there to oblige. Filled with ambitious plans to expand, it began making acquisitions throughout the US and Canada. But when China caused the Rare Earth Elements price to crash, the US industry went with it. Molycorp went bust, and its investors and the government lost faith in the sector.

Image taken from ResearchGate

#An environmental challenge

Despite their name, Rare Earth Elements are not actually rare. They’re found all over the globe, but producing them is complex. Usually scattered amongst other materials means it takes time and energy to separate them into usable elements. The process involves acid baths and radiation, which is dangerous and bad for the environment. Just ten years ago, the Chinese government predicted the Rare Earth Elements industry was producing over 22 million tons of toxic waste annually. With climate change agenda’s and environmental protection at the forefront of our minds, this would have to be addressed before large-scale rare-earth mining could be a viable proposition in the US.

Nonetheless, these elements are in demand because they’re needed to solve the ongoing problem of pollution and achieve advances in creating a greener planet.

#Future demand outlook

Covid-19 has suppressed global demand for rare earths this year, but demand is expected to rebound rapidly in the next couple of years. Followed by a steady rise into the 2030s.

“Looking ahead to 2030, it is exceptionally challenging to foresee how, under any realistic scenario, the supply side of the rare earth industry will be able to keep up with rapidly growing demand for magnet rare earths (i.e. neodymium, praseodymium, dysprosium and terbium).”

– Adamas Intelligence

This future demand emphasises the global requirement for Rare Earth Elements and the importance of reducing China’s control of the market. It’s a sector investors should be keeping a close eye on as Adamas Intelligence also forecasts that “global shortages of NdFeB alloy and powder will amount to 48,000 tonnes annually by 2030—roughly the amount needed for some 25 to 30 million electric vehicle traction motors.”

As if that wasn’t shocking enough. The report also found:

Constrained by a lack of new primary and secondary supply sources from 2022 onward, global shortages of neodymium, praseodymium and didymium oxide (or oxide equivalent) will collectively rise to 16,000 tonnes in 2030, an amount equal to roughly three-times MP Materials’ annual output, of neodymium and praseodymium oxide (or oxide equivalents).

This very real and looming threat of global shortages will wreak havoc on carbon-reducing efforts to industry and show a desperate need for new mines and players in the West.

#Bringing US production and processing home

Rare earths have already proven their worth time and again, and as they’re now present in so many critical industries, it seems like R&D in this area should be a given. Unfortunately, that’s not the case. China’s dominance puts untold risks on the supply chain, deterring many Western companies from progressing in their R&D efforts. Until a low-risk, non-Chinese supply chain exists for rare earths, many Western companies will leave rare earth innovation to the Chinese.

Together, the US and Canada are currently working at the government level regarding Rare Earth Elements. Canada has both potential mines, as well as analytical and downstream processing capability. In order to create a robust, reliable supply chain in North America, multiple sources will be necessary for each stage.

Nowadays, so many companies operate internationally, meaning it’s very difficult to limit business activity entirely to the US. Even if this wasn’t an issue, if the companies are publicly listed then it becomes impossible to stop Chinese or other foreign operators from buying shares in them. The fact China can manipulate prices and have such control over supply chains is indeed worrying. It seems sensible for the US to bring domestic production back to fruition, but it’s likely to be a long process and will need government support to forge ahead.

The US could retake a position of strength with many benefits if the rebuilding of a domestic Rare Earth Elements industry can be achieved. By securing defense supply chains, US companies could innovate freely again, and US allies would have reason to collaborate again.

Thankfully, it looks as if this is exactly what the US and Canada would like to do.